“Innovation must start with our youngest minds and thinkers.”

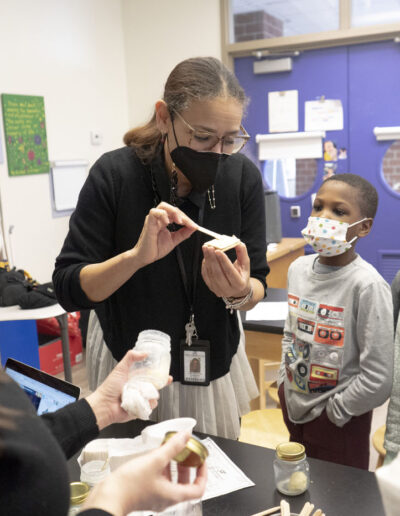

This philosophy drives Lower School Science teachers, Julie Pugkhem and Yi Li, who are tasked with fostering students’ curiosity and critical thinking skills.

Now in her eighth year at D-E, Julie works with students from Pre-K through first grade, providing the youngest of students their first opportunity in scientific inquiry.

“First and foremost, we build a love for all parts of science,” Julie explained, “we start off the year by asking: what is a scientist? What tools do they use, and how do they perform research?

I try to relate to them that they are, in fact, scientists, and everything that they do every day is basically science. For example, I don’t necessarily talk about molecular structure, but I introduce the properties of matter, so they are familiarized with those ideas through their five senses.”

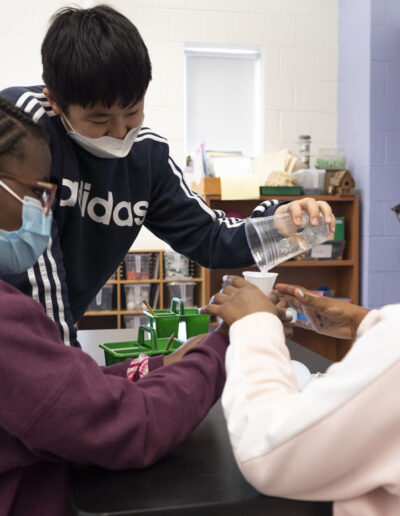

As students move up in grade-level, project-based learning becomes an important part of the curriculum. In their first year teaching at D-E, Yi Li brings a wealth of knowledge of integrating technology into the classroom. The long-running “House Project” offers second graders an opportunity to learn about different cultures and house construction. To build their models of houses in the Antarctic, students determine the factors that keep a building insulated. Using bluetooth temperature probes, typically seen in Middle and Upper School classrooms, second graders learn to test for humidity and acquire a new skill set along the way.

However, science can be frustrating, and preparing students for trial and error is part of the pedagogical process. During a buoyancy activity with tin foil boats, Julie had students make predictions whether the boat would sink or float. Although students can expect their predictions to be incorrect, Julie emphasizes to her students that:

“Scientists have to go through trial and error. Otherwise, we’d know everything. It’s kind of like life. We have those situations of a caterpillar that never turns into a butterfly, but what we can do is talk about what may have happened and what we can try next time.”

Teaching students about scientific inquiry requires modeling empathy for the challenges that they may face.

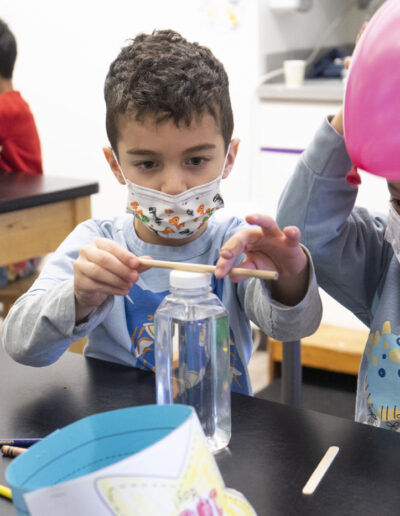

At the same time, Julie and Yi are learning right along with their students. Introducing new tools like TinkerCAD, a 3D-modeling program, and Scratch Jr., an age-appropriate coding software, comes with new learning curves. As Yi was test-piloting TinkerCAD, she initially encountered concerns with the software:

“I thought, if I’m having trouble with this, then the students will too. When I brought it [TinkerCAD] to class, everyone was very patient. The students worked really hard and helped each other. I think they’re more comfortable with trial and error in the technology world, and we’re the technology immigrants.”

In our increasingly digital and globalized world, students can demonstrate resilience for these kinds of familiar challenges. The task then becomes encouraging students to access that same resilience for new material and situations. Rather than framing science as a discipline only concerned with facts, Yi and Julie teach science as a space for ongoing questions and experimentation. After all, the scientific method always begins with a question.

As the weather becomes warmer, Yi and Julie are eager to bring the students outside for more hands-on learning. How a plant grows and how some insects undergo metamorphosis are just a few of the exciting topics that students can look forward to. No matter the unit, what Yi and Julie are always certain of is students’ enthusiasm to listen and take ownership of their learning.